We solved trust for AI Agents in 1973 (we just forgot)

Structural pessimism

Everyone is worried about making AI agents trustworthy. Ideally, agents should be aware of context and never make irreversible mistakes in or near production systems.

The problem is even sharper in data engineering. Unlike bugs, which can usually be rolled back by redeploying code, data errors mutate shared historical state that downstream consumers implicitly trust. Plus, there is always the sensitive nature of data from a legal standpoint.

Without trustworthiness, they say, agents cannot act on production data and infrastructure, which means that they cannot move from assistance to full automation.

We think this is the wrong problem to solve. We’ve spent enough time working in data to know that good data management simply does not happen by assuming competent and well-behaved actors. On the contrary, good systems don’t expect users to be trustworthy and are built to contain the side effects of their mistakes.

Agentic data engineering will not come from trusting AI. It will come from untrustworthy AI agents working with data platforms that enforce isolation, correctness and rollback by default.

Databases made concurrency safe a long time ago

We know that solving this problem is possible because it already happened once, with databases. Mature SQL systems (such as Postgres) let many users work on the same tables while giving each of them the experience of working alone.

In the picture above, User 1 (U1) is updating some tables and then returning the balance. From the POV of U1, the database gives him the illusion of being the only user in play:

- U1 does not need to assume that their own code is correct. If the update logic violates a constraint, the transaction is aborted and none of its effects become visible.

- U1 does not need to assume that other users are well-behaved. U2 may be running buggy code or issuing conflicting updates. None of this leaks into U1’s view of the data, there is no need to know what U2 is doing.

- U1 does not need to reason about physical storage or execution details. Locking, versioning, and rollback are handled by the system.

The database enforces three separate kinds of isolation:

- Data isolation. The balance that U1 reads comes from a consistent snapshot of the database. Intermediate states from concurrent updates from U2 are never exposed.

- Execution isolation. U1’s query runs as an independent execution. Resource management, locking, and scheduling prevent other queries from interfering in ways that would change results or corrupt state.

- Abstraction isolation. User code never expresses locks, snapshots, or storage layout explicitly. Applications describe what to read or write, not how isolation is achieved or data is physically stored.

Users interact with the database through declarative SQL statements in which they describe what data should be read or modified, but never manipulate storage, execution order, or locking directly. It’s the database (not the users) that enforces consistency through transactional execution, including automatic rollback on failure.

When nothing fails, these guarantees are invisible. But they are vital when things go wrong. When an update fails, the system rewinds to a known-good state preventing partial changes to leak. Data can always be inspected retroactively, because the database can reconstruct a consistent historical view through point-in-time queries.

Why can only SQL people have nice things?

This is OLTP, but let’s look at OLAP. Most analytics workloads are implemented as data pipelines spanning multiple steps and often living in multiple systems. The goal of a pipeline is to ingest, clean, transform, and moving data from table A to B to C.

Pipelines were never designed for untrusted concurrency. Their abstractions and infrastructure are fragmented across runtimes, libraries and languages, like Python and SQL. Consequently, they are triggered manually, reviewed informally, and fixed cautiously.

Take this (stripped down) AWS reference implementation for Python pipelines using Airflow: the pre-processing step reads from S3, transforms the data using Pandas, and writes multiple output files back to object storage. The code manipulates the physical layer directly by reading and writing files on S3, leaving storage and transaction details in the hands of users (typically, not a good idea!).

Imagine a scenario where several AI systems are iterating at the same time against the same intermediate assets (e.g. one building reports, the other one doing an hyper-parameter search). In this setting, each agent reads and writes files directly in shared object storage, with no transactional boundary spanning the pipeline.

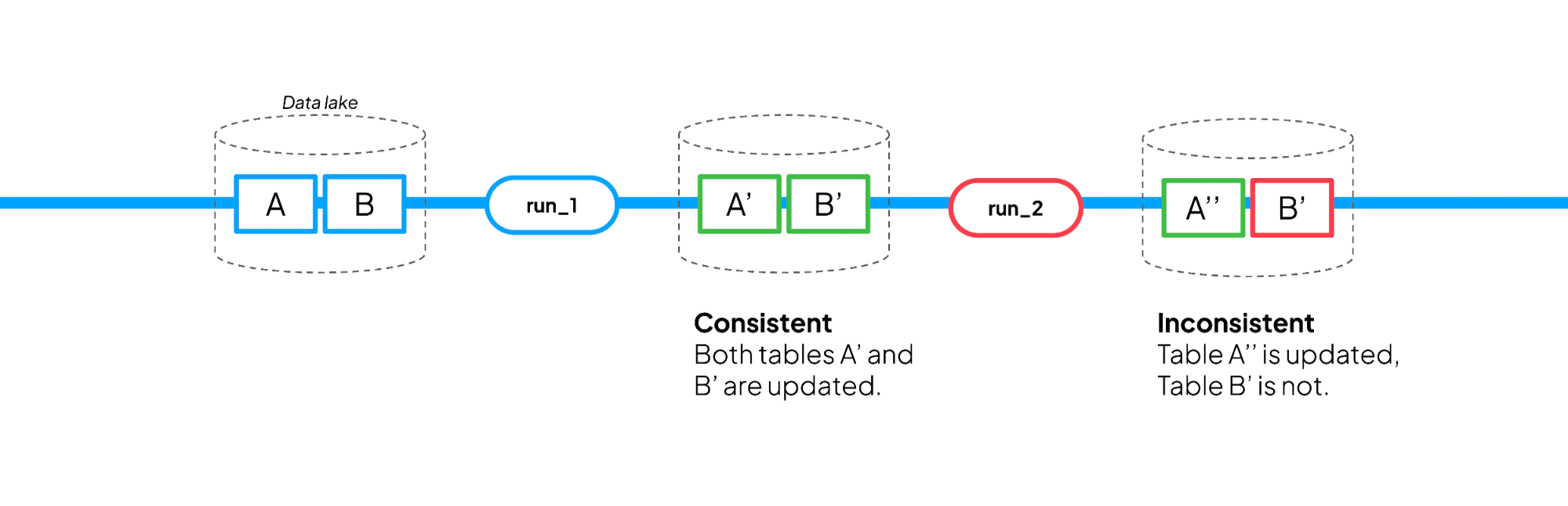

An AI agent triggers the pipeline for the first time. This first execution, run_1, succeeds: the pipeline reads raw data from s3_in_url, performs transformations in-process, and writes two derived datasets back to object storage: validate_df (call this Table A) and train_df (call this Table B). The system now exposes A′ (the new version of validate_df) and B′ (the new version of train_df) together. Downstream consumers see a consistent result.

A short time later, a second agent independently triggers the same pipeline. This second execution, run_2, fails after writing validate_df but before writing train_df. Because each write is handled independently, the system now exposes A′′ (a newer version of validate_df) alongside B′ (the older version of train_df).

From the consumer’s point of view, nothing is wrong: both outputs exist and are valid files. But they are not: from the producer’s point of view, the pipeline is half-done, and downstream system would read the inconsistent state A′′ with B′.

In other words, the system as a whole is not safe, unless we assume perfect coordination between users, extreme competence, and no malicious intent. While some human teams could arguably possess all of these fine qualities, a fleet of AI Agents simply will not.

A Lakehouse for AI Agents

To have agents working freely on the data pipeline, we would need to build a system that can handle concurrency correctly. The problem is that a Data Lake is not a Database. In a monolithic, database, storage and execution are vertically integrated, allowing the system to present each user with a consistent view of data and to publish changes atomically.

A lakehouse breaks that assumption by design, because storage and compute are decoupled: data lives in object storage, while execution happens in external engines, schedulers, different runtimes and in different languages (SQL queries and Python scripts). So what do we do?

Step 1: Declarative I/O and Isolated compute

To bring lakehouse pipelines closer in spirit to transactional workloads, we need declarative I/O and isolated compute. The goal is to shrink the surface the agent can touch, so the system can enforce isolation and permissions at the API layer because the agent never writes files or configures infrastructure directly.

This means that pipelines should consume and produce tables, not files. User code declares what data is transformed, while the system owns when, where and how those results are materialized. Let’s rewrite the AWS example from above in a declarative way by slightly augmenting standard Python functions. This is the same process written in Bauplan.

In this code, inputs and outputs are tables, not files: I/O is the platform’s responsibility, leaving user reasoning entirely at the logical level, not the physical one. It is up to the system to read/write the correct physical representation backing the specified tables.

This system also ensures process isolation. The functions are executed as separate, containerized functions in a FaaS-like manner and the function environments are declaratively specified in code through a decorator (i.e. @bauplan.python ).

This allows each pipeline step to run in a fully isolated runtime so that different languages, versions, and dependencies cannot share a process. Isolation prevents runtime conflicts and constrains what agents can execute by design (i.e.: packages are platform’s responsibility, making it easy to blacklist undesired dependencies).

Step 2: transactional pipelines

Declarative I/O and isolated compute constrain the execution of individual steps, but they do not yet define when the results of a pipeline become visible.

To address directly the problem, we need transactional pipelines. To be transactional a pipeline must be atomic across multiple writes: when a pipeline runs and modifies three tables across SQL and Python steps, either all three writes happen or none do.

To achieve this in a lakehouse, we can borrow a familiar abstraction from software development and treat table writes as immutable changes grouped into a run. A pipeline run executes in isolation, produces new versions of its outputs, and only publishes them if the run completes successfully. Practically, let’s now run our pipeline in a non-linear way. This time, note that tables get versioned like code with Git: a table change is a commit and changes can be sandboxed in a branch (which can be merged at a later time).

As above, a first agent triggers run_1 to update A and B, then a second agent triggers run_2. Except that this time all updates happen on a “transactional branch”, which is not visible on the main production line until it is merged by the system: when run_1 succeeds, its branch is merged and A′ and B′ appear together as an atomic change to production. Vice versa, when run_2 fails, its branch is never merged and A′′ never reaches the main branch. The main branch continues to expose A′ and B′ exactly as if run_2 never happened.

If a pipeline run is treated as a single transactional unit, agents can run concurrently without coordination. They can explore, retry, and fail, but production only advances through successful, atomic merges. As in the case of our initial OLTP setup, no downstream consumer will ever see partial state.

In this model, point-in-time views come for free and every successful commit marks a consistent snapshot of the entire lake. We can now have trustworthy agentic data pipelines without trustworthy agents.

Move fast and trust no one

Focusing on agent trust pushes the revolution years down the line, encouraging us to wait for perfect models before letting agents touch real data.

In practice, a focus on agent trust often turns into a focus on constraining intelligence. Agents are limited to predefined workflows, forced into rigid templates, restricted to narrow toolchains, or allowed to explore only a small portion of the vast manifold they encompass.

We already see this in read-only agents and heavily scripted “agentic” systems that are little more than parameterized macros with a language model on top. These approaches reduce risk by narrowing the space of possible actions, but they do so by deliberately suppressing the very thing that makes AI powerful: open-ended exploration.

To all of this we say: bo-ring. It is a remarkably uninspiring way to think about this moment. Intelligence is what makes this shift so momentous. We should not be designing systems that keep agents on a short leash. We should be designing systems that assume agents will explore widely, reach dead ends, make incorrect changes, and often do the wrong thing, and still remain safe.

The right question is not how to make agents trustworthy, but how to build data systems that do not assume trust at all. In fact, they should assume the opposite: treat every actor as fallible, isolate their actions by default, and ensures that mistakes remain local. That is what allows many actors to work concurrently without threatening the consistency or integrity of the overall system.

If you want to know more, we will be on the AAAI26 stage at the end of January discussing our full-length position paper on AI trustworthiness in the lakehouse. If you are impatient and just want to run agents for data engineering tasks, our first self-healing pipeline flow is now available on GitHub.