Rethinking Data Pipelines in Python

Intro

Python became the default language for ML and AI because it gave developers a single, expressive environment for modeling, experimentation, and deployment.

Data engineering never made the same transition. Most teams still run pipelines where the orchestration is Python-friendly, but the actual data processing still depends on JVM engines, Spark clusters, container fleets, or warehouse-specific SQL dialects. The result is a split-brain model: Python for the orchestration plane, something entirely different for the data plane.

This is what we are going to talk about.

The unstoppable rise of Python

Over the past 15 years Python evolved from a scripting tool into the most widely used language, especially in AI, machine learning, and data science (2025 Github Octoverse).

Besides Python’s syntax being more concise and approachable than many other languages used for scientific computing or production infrastructure (C++, Java, Scala), I think that one of the main reasons for it Python being successful is this: you can do pretty much everything in it, from data cleaning to model building to deployment. You can use NumPy and SciPy for vectorized numerics, Pandas and Polars for tabular data , Scikit‑learn for ML, and PyTorch for deep learning.

Orchestration followed a similar trajectory. As the industry moved beyond cron jobs and GUI-based ETL tools, developers gravitated toward workflow systems that treated pipelines as code. Python became the natural choice for this style of orchestration because it was flexible, general-purpose, and already widely adopted. Airflow was the first major example, and later Prefect pushed the idea further by letting teams express scheduling, retries, and dependencies as ordinary Python functions.

The result was that, by the time organizations began operationalizing ML workloads, the orchestration plane already lived in the same environment as their experimentation. Modeling and orchestration spoke the same language.

But Not for Data

The data layer, however, did not. Even if Python is the go-to language for so many data related jobs, developers are pushed to JVM-based engines like Spark, Presto or Trino, as data volume and workload complexity grew. Why, you may ask? There are few reasons.

First, when JVM-based big data engines were first developed machines didn’t use to be as large as today. A lot of data workloads (especially those involving heavy transformations) that today could comfortably fit in a large machine, required distributed processing. Python’s runtime and concurrency model made it a poor fit for these early distributed-compute systems: it is interpreted, dynamically typed, and slower on CPU-bound workloads than JVM languages, which benefit from JIT compilation and predictable memory management.

Second, the way big-data engines interact with storage makes Python inefficient at scale. Most data catalogs and table formats were designed for big-data engines. Hive Metastore, Glue Catalog, Apache Iceberg, and Delta Lake perform metadata planning, partition pruning, predicate pushdown, and snapshot management inside JVM-native engines.

Without all these nice things, the Python developer is left with reading raw Parquet or CSV files from S3 with not optimizations. As a result, operations that should read a few partitions end up scanning far more data than necessary, which again is a heavy tax to pay at scale where having high I/O, slow performance, and wasted compute resources is more hurtful.

Third (but it’s a less data-specific reason), using Python in large or cloud-based data pipelines often runs into dependency management problems. The broader Python ecosystem has thousands of packages and different pipelines or services need different versions of libraries which can increases friction when deploying Python pipelines in shared or cloud environments (”it works on my machine!”).

So in the end, the common knowledge is that when it comes to data processing Python is for boys, the JVM is for men.

The great divide

The result is that data pipelines become hybrid systems by necessity: Python for orchestration, Spark or Trino for the actual execution, and a JVM-native catalog to manage schema evolution and table metadata.

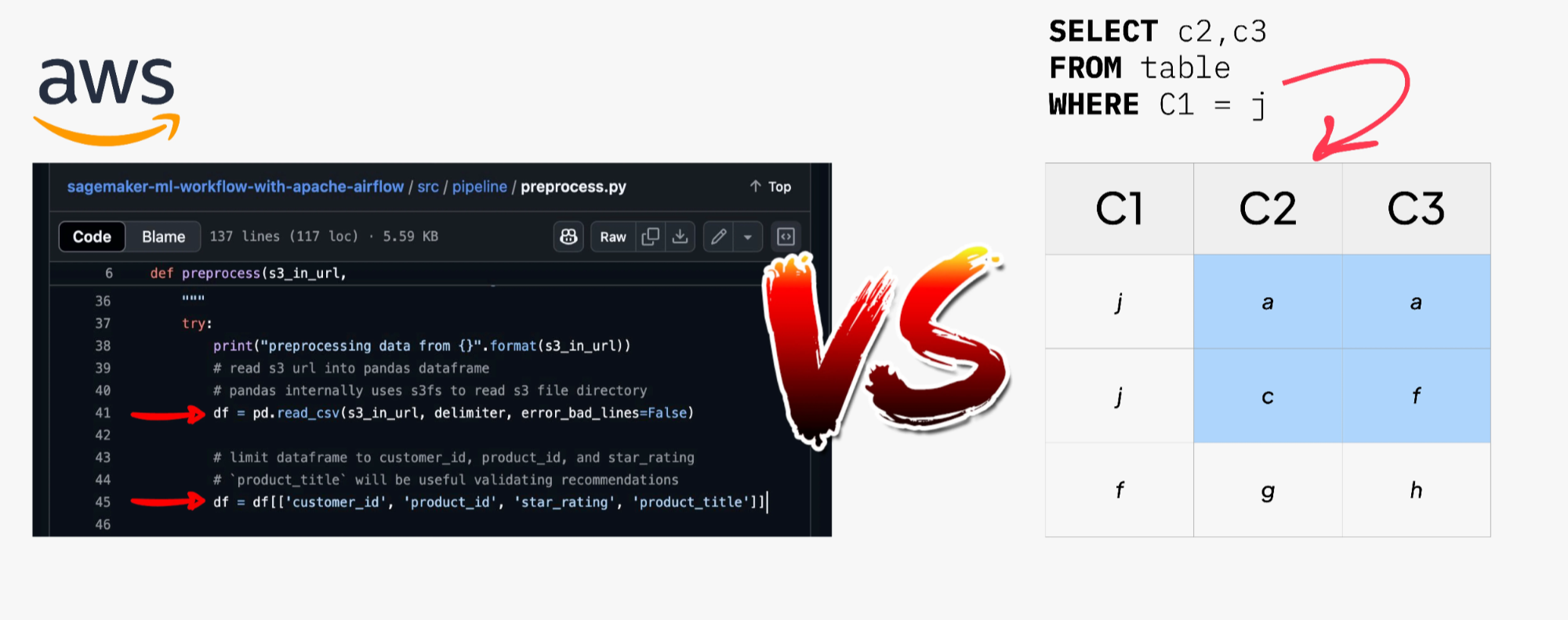

So even though control flows, retries, and error handling happen in Python, the core transformations live in distributed JVM or SQL engines and require non-trivial special knowledge for performance tuning and understanding how the catalog interprets snapshots and manifests.

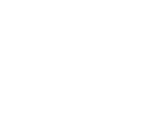

Python APIs like PySpark might give the impression that you can stay within a single language, but they are thin wrappers over a JVM runtime. When something happen, the abstraction leaks revealing the engine beneath them, forcing developers to switch mental models constantly.

The real issue is that Python became the control plane but never the data plane: the pipeline starts in Python, then falls through a trapdoor into a JVM engine that owns planning, optimization, metadata, and execution.

This fragmentation is one of the primary reasons for pipelines to become fragile. Pipelines break not because orchestration tools are weak, but because engineers lack visibility into what’s happening inside the data itself (late-arriving records, partial batches, silent schema drift, column-level inconsistencies, file skew, or misaligned metadata).

Everything as Python

Changing this requires a system with needs where the planner and the runtime are native to Python, where table operations and transformations are expressed and executed in Python, and where the guarantees of a Data Lakehouse (schema evolution, correct snapshotting, ACID-like commits) are preserved.

Bauplan is built around that premise.

The control plane parses user-defined Python functions, builds a DAG and a logical plan from their dependencies, and compiles that plan into concrete operations over tables, metadata, and storage. The runtime then executes those operations as isolated functions inside a Python-native runtime that scales vertically, loads only the required packages, and works directly over Arrow data rather than serialized blobs.

Instead of relying on Spark or Trino, SQL and Python run in the same execution environment, pushdowns happen before touching storage and data is exchanged throughout the pipeline as Arrow buffers, rather than through serialization.

For developers, this collapses the workflow into one simpler mental model:

- Transformations and tests are just functions: a transformation is a Python function that receives a dataframe and returns a dataframe. An expectation test is a Python function that receives a dataframe and returns a boolean.

- Data versioning is built-in. Data versioning is built-in and comes from the catalog rather than from ad hoc conventions. In Bauplan, every run executes on its own data branch, and merges only on success. This means a pipeline never writes directly into production tables; it writes into an isolated lineage that looks like production but cannot affect it. The catalog tracks the entire state of the tables on that branch, so each transformation produces a new snapshot with a clear parent–child history. If a step fails, the branch simply remains where it stopped, preserving the exact intermediate state for debugging. If the pipeline succeeds, the system performs a single atomic merge that publishes the new snapshots as a coherent unit. There is no need for manual staging tables, timestamped folders, or naming tricks. Versioning is structural, not procedural, and pipelines inherit safety by construction rather than by discipline.

- Transformations become replayable. Every transformation is replayable because the code, the data version, and the environment are all fixed and expressed as Python. The control plane snapshots not just the function source but the exact interpreter version and package set attached to it, and the data plane executes it against a specific catalog snapshot. That triple (code, environment and data) fully determines the output. There is no hidden optimizer, no implicit state inside a long-running cluster, and no external engine whose behavior changes between runs.Debugging becomes a matter of re-running the same function on the same snapshot. If a pipeline step produced an unexpected result, you do not reconstruct context by chasing Spark logs, catalog manifests, or temporary staging files. You simply replay the function on the branch where it failed. The same code runs in the same environment against the same bytes of data, so you can get the same behavior.

At the orchestration layer, tools like Prefect already give teams a clear Python interface for scheduling and control flow.

What previously required orchestrating Python around a separate JVM or SQL engine becomes a single workflow because the expression layer is unified. Developers define orchestration logic and data logic in the same language, with the same abstractions, while execution is handled by the data plane without leaking its internal complexity. The pipeline no longer spans Python code, Spark notebooks, SQL scripts, and catalog commands: it becomes one coherent system whose control flow and data transformations are both expressed in Python.

This shift resolves two persistent sources of fragility:

- Data manipulation becomes safer because each operation runs on its own branch, produces explicit snapshots, and merges only when the entire run succeeds.

- Operational workflows become simpler because orchestration frameworks like Prefect manage scheduling, retries, and state transitions entirely in Python, and all data logic t is exposed through the same interface. The underlying execution engines may differ, but the developer experience does not.

Once both layers speak Python, the amount of code required drops sharply. A full pipeline with tests, isolation semantics, and write-audit-publish behavior becomes a small set of ordinary functions. Task-level retries from the orchestrator combine with data-level atomicity from the catalog, so failures leave behind a preserved branch rather than partial writes scattered across tables.

See you, Python cowboy

If you want to see what this looks like in practice, the full example pipeline is available in our open-source repo: https://github.com/BauplanLabs/wap_with_bauplan_and_prefectAnd for production integration, the Prefect–Bauplan guide walks through configuration, deployment, and best practices: https://docs.bauplanlabs.com/integrations/orchestrators/prefect